Bombing of Tokyo

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The bombing of Tokyo, often referred to as a "firebombing", was conducted as part of the air raids on Japan by theUnited States Army Air Forces during the Pacific campaigns of World War II. The U.S. mounted a small-scale raid on Tokyo in April 1942, with large morale effects. Strategic bombing and urban area bombing began in 1944 after the long-range B-29 Super Fortress bomber entered service, first deployed from China and thereafter the Mariana Islands. B-29 raids from those islands commenced on 17 November 1944 and lasted until 15 August 1945, the day Japan capitulated.[1]The Operation Meetinghouse air raid of 9–10 March 1945 was later estimated to be the single most destructive bombing raid in history.

[edit]Doolittle RaidMain article: Doolittle Raid

The first raid on Tokyo was the Doolittle Raid of 18 April 1942, when sixteen B-25 Mitchells were launched from USSHornet to attack targets including Yokohama and Tokyo and then fly on to airfields in China. The raid was the retaliation against the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor. The raid did no damage to Japan's war capability but was a significant propaganda victory for the United States.[2] Launched prematurely, none of the attacking aircraft reached the designated airfields, either crashing or ditching (except for one aircraft which landed in the Soviet Union, where the crew was officially interned and secretly repatriated). Two crews were captured by the Japanese in occupied China and later killed in violation of the Geneva Convention protocols for POW's.[3] [edit]B-29 raidsThe key development for the bombing of Japan was the B-29 bomber plane, which had an operational range of 3,250 nautical miles (6,019 km) and was capable of attacking at high altitude above 30,000 feet (9 km) where enemy defenses were very weak. Almost 90% of the bombs dropped on the home islands of Japan were delivered by this type of bomber. Once Allied ground forces had captured islands sufficiently close to Japan, airfields were built on those islands (particularly Saipan andTinian) and B-29s could reach Japan for bombing missions. The initial raids were carried out by the Twentieth Air Force operating out of mainland China in Operation Matterhorn under XX Bomber Command, but these could not reach Tokyo. Operations from the Northern Mariana Islands commenced in November 1944 after theXXI Bomber Command was activated there.[4] The B-29s of XX Bomber Command were transferred to XXI Bomber Command in the spring of 1945 and based on Guam.[citation needed] The high altitude bombing attacks using general purpose bombs were observed to be ineffective by USAAF leaders. Changing their tactics to expand the coverage and increase the damage, Curtis LeMay ordered the bombers to fly lower (4,500–8,000 ft, 1,400–2,400 m) and drop incendiary bombs to burn Japan's vulnerable wood-and-paper buildings.[5] The first such raid was in February 1945 when 174 B-29s destroyed around one square mile (3 km²) of Tokyo. The next month, 334 B-29s took off to raid on the night of 9–10 March (Operation Meetinghouse), with 279 of them dropping around 1,700 tons of bombs. Fourteen B-29s were lost.[6] Approximately 16 square miles (41 km2) of the city were destroyed and some 100,000 people are estimated to have died in the resulting firestorm, more immediate deaths than either of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.[7][8] The US Strategic Bombing Survey later estimated that nearly 88,000 people died in this one raid, 41,000 were injured, and over a million residents lost their homes. The Tokyo Fire Department estimated a higher toll: 97,000 killed and 125,000 wounded. The Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department established a figure of 124,711 casualties including both killed and wounded and 286,358 buildings and homes destroyed. Richard Rhodes, historian, put deaths at over 100,000, injuries at a million and homeless residents at a million.[9] These casualty and damage figures could be low; Mark Selden wrote in Japan Focus:

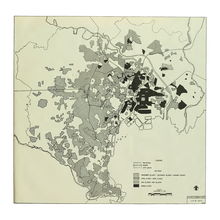

The destruction and damage were greatest in the parts of the city to the east of the Imperial Palace.[citation needed] Over 50% of Tokyo was destroyed by the end of World War II.[citation needed] The firebombing of Tokyo on the night of 9/10 March 1945 was the single deadliest air raid of World War II;[11] greater than Dresden,[12] Hiroshima, or Nagasaki as single events.[13][14] [edit]Partial list of B-29 missions against Tokyo

[edit]Other attacksAdditional missions against Tokyo targets were carried out by twin-engine bombers and by fighter-bombers.[16] 72rd Wing, 313th Wing, and 314th Wing: Order No. 39, aircraft 229. An attack on Tokyo, February 1945. The original intent is to attack the "highest priority target in Tokyo" which is the Musashino Plant of the Nakajima Aircraft Engine. It was important because Tokyo was considered a powerhouse. It is "full of businesses and key industries such as machines and machine tools, electronics, precision instruments, petroleum, aircrafts and their parts." The attack would be hitting Japan's "war machine." There were a couple different bombs selected for use: one 500 pound general-bomb on every craft, the M-69 incendiary bomb, and the E-46 incendiary cluster. The primary target was Tokyo's urban area, the secondary was the same as the primary, the last resort was any industrial city. The outcomes of the mission: 88% destroyed, a total of 28,000,000 sq ft.[17] [edit]Immediate effects and aftermath of the firebombingsDamage to Tokyo's heavy industry was slight until firebombing destroyed much of the light industry that was used as an integral source for small machine parts and time-intensive processes. Firebombing also killed or made homeless many workers who had been taking part in war industry. Over 50% of Tokyo's industry was spread out among residential and commercial neighborhoods; firebombing cut the whole city's output in half.[18] The Imperial Palace was surrounded by areas destroyed by firebombing. The main Palace itself (Kyūden), home of the Imperial General Headquarters, took heavy damage by fire, even though bombing it was specifically prohibited by USAAF order. Emperor Hirohito's viewing of the destroyed areas of Tokyo in March 1945, is said to have been the beginning of his personal involvement in the peace process, culminating in Japan's surrender six months later.[19] [edit]Postwar recoveryAfter the war, Tokyo struggled to rebuild. In 1945/1946, the city received a share of the national reconstruction budget roughly proportional to its amount of bombing damage (26.6%), but in successive years Tokyo saw its share dwindle. By 1949, Tokyo was given only 10.9% of the budget; at the same time there was runaway inflation devaluing the money as Japan was spending more than it was bringing in from taxes. Occupation authorities such as Joseph Dodge stepped in and drastically cut back on Japanese government rebuilding programs, focusing instead on simply improving roads and transportation. Tokyo did not experience fast economic growth until the 1950s.[20] Between 1948 and 1951 the ashes of 105,400 people killed in the attacks on Tokyo were interred in Yokoamicho Park in Sumida Ward. A memorial to the raids was opened in the park in March 2001.[21] [edit]Postwar debate and legal disputeIn 2007, Japanese Prime Minister Abe Shinzō apologized in print, acknowledging Japan's bombing of Chinese cities beginning in 1938, killing civilians. He wrote that the Japanese government should have surrendered as soon as losing the war was inevitable, an action that would have prevented Tokyo from being firebombed in March 1945, as well as subsequent bombings of other cities.[22] Thereafter, survivors banded together and unsuccessfully sued the Japanese government for compensation; however, efforts continue.[23] After the war, Japanese author Katsumoto Saotome, a survivor of the 10 March 1945 fire bombing, helped start a library about the raid in Koto Ward called the Center of the Tokyo Raid and War Damages. The library contains documents and literature about the raid plus survivor accounts collected by Saotome and the Association to Record the Tokyo Air Raid.[24] [edit]See also[edit]Notes

[edit]Further information[edit]Books

[edit]Web

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||